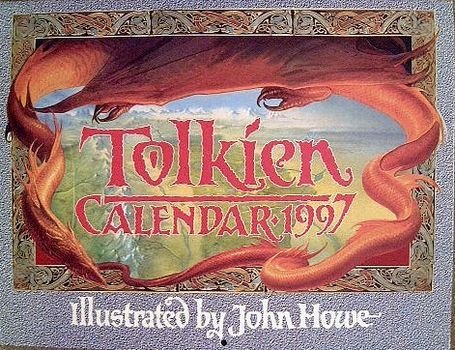

1997 Tolkien Calendar

The 1997 Tolkien Calendar. HarperPrism, New York, NY. ISBN: 0-06-105525-5.

Reviewed by Paula Disante

Oh, To Be in Middle-earth

This year’s Tolkien calendar, illustrated by John Howe, features a return to the stapled-in-the-middle style, a change from the spiral bound calendars of the past two years. It also is presented in a horizontal format, as opposed to the square shapes of recent memory. The background behind each painting, including the cover, is a drab, pebbly gray, but this is easily ignored as one takes the yearly pictorial journey through Middle-earth.

The cover painting, rimmed by a border of skillfully rendered Celtic knotwork, is a promising aerial view of the Misty Mountains, Mirkwood and the Lonely Mountain. Unfortunately, this is all but obliterated by giant title lettering in resplendent red. Never have we been more boldly told that this is indeed the Tolkien calendar. The hard-to-see central landscape is also bordered by a twisting, golden Smaug. The dragon is quite an achievement, his one quirk being his sleepy face. Smaug would have been more effective with a more sinister countenance. Howe seems to be trying for it, but doesn’t quite pull it off.

January: “Descent to Rivendell” was so blatantly not originally intended as a calendar piece, but as a book cover, that a poem (the Elves’ gentle mocking of Bilbo and the Dwarves) had to be printed on the left-hand side of the picture to hide its gaping emptiness. Only very vague mountains are visible in the upper portion of this “back cover” of the painting. Running down the spine of the piece, and flanking both the extreme left and right sides are stone pillars with dragon-crowned capitals, imaginatively painted.

The right-hand side of the painting is well done. A light rain is in the air as Bilbo and one of the Dwarves make their way down into the valley of Rivendell. Rocks and trees and lush green grasses enrich this part of the work. The Last Homely House, perhaps a tad too much like an Austrian castle in design, nevertheless makes a beckoning destination in the center background.

Despite some minor peculiarities in perspective, February’s “An Unexpected Party” works quite well. A satisfying blend of warm and cool (almost too cool) light helps establish the tensions in the scene. Bilbo, looking a bit like a deer caught in the headlights of a pickup truck, is an overwhelmed host to a roomful of music-making Dwarves. Gandalf, puffing a pipe and intently watching the proceedings, sits like a silver phantom near a large round window.

Although the viewer might not necessarily agree with Howe’s depiction of Bilbo and the Dwarves, this remains an effective painting. It is interesting to note that Bilbo has an unusual amount of framed paintings on the walls of his home — quite the cultivated gentlehobbit!

March: “The Treason of Isengard” This is an odd title, since the painting has nothing to do with Isengard. It is, instead, an indifferent rendering of Edoras. The city and the great hall are situated atop a little hill that is altogether too steep – and too tiny – to have any real correlation to what Tolkien described.

The mountains looming in the background, nearly obscured by a blanket of cloud, seem unnaturally top-heavy. Almost unnoticed in the lower right corner is what appears to be a small squad of mounted soldiers. The far background is suitably atmospheric, but there’s little here to stir the blood. An inoffensive, but not particularly interesting, entry.

April: “The War of the Ring” The location of this scene in the midst of a river or pool of water isn’t exactly what Tolkien described, but it’s a handsome treatment all the same. Howe puts both Frodo and Sam up in the tree on the left of the painting, when in fact it was only Sam who climbed up into the branches for a better look. The raging Oliphaunt would have been a much more present threat if he had not been placed so deep in the background. This is not the best version of this scene ever painted, but it acquits itself well.

May’s “Tolkien’s Middle-earth” map is interesting for the small pictures bordering it. The map itself is visually pedestrian, an unexciting rendition of Tolkien’s classic map. But the narrow borders contain some notable Middle-earth images – on the left, the Dark Tower, and below that a pair of Nazgûl in flight. On the right, Gandalf rides Shadowfax to Minas Tirith. Below the map are tiny portraits of Gandalf and Gollum, the former more successful than the latter. And above is a three-part idyll of Rohan, the Shire, and (possibly) Gondor. It is a pity these border pictures were not rendered larger. They are far more interesting than the map itself.

June’s topsy-turvy “Treebeard” may claim the distinction of the first Middle-earth calendar painting to be published upside down. Exactly how this went unnoticed by the publishers remains a mystery, especially since the inversion so clearly puts the artist’s signature in the upper right corner of the painting.

The piece itself, even when viewed the correct way, is unremarkable. Perhaps that is why it was inadvertently inverted. Howe uses smoky yellow-grays throughout, which causes most of the composition’s elements to appear to blend into one another. This markedly compresses the depth of field of the picture, and so there remains little sense of “place.” Treebeard himself, what little we see of him, is forgettable – not offensive, but simply not very distinctive. Perhaps this is better viewed upside down….

July: “A Hobbit Dwelling” Not just any hobbit dwelling, this is clearly Bag-End as originally visualized by Tolkien and here given a full-blown painted treatment. Howe does a good job with the warm, softly glowing surfaces of wood, and the polished stone floor. The open door allows a view of the land beyond: dream-like and indistinct.

Without a hobbit in the picture for scale, Bag-End’s barrel-vaulted ceiling seems more cavernous than it ought, and the door looks unnaturally large. But even Tolkien’s original version, with Bilbo in the picture, was not to proper scale, so this is a minor quibble of little consequence in an otherwise fine painting.

August: “Niënor and Glaurung” The most striking thing about this picture is the use of the complementary colors of blue and orange for a strong visual impact. The natural elements are remarkably effective. Glaurung, sad to say, is less so. Where the dragon’s eye should be daunting and baleful, it is instead bored and disinterested. Glaurung lies draped on a hilltop, looking much more like an iguana with a pituitary problem than a dragon. Niënor, though, has suitably fallen under Glaurung’s evil spell. And if there is one thing Howe paints effortlessly, it is long, lush, richly-colored grassland.

Howe usually pulls it all together in one painting in each of his calendars, and September’s “Ungoliantë and Melkor” holds that distinction. In this triptych, the left and right panels show stark, forbidding gray walls. Before the walls are leaden mists and the menacing glow of lava from rents in the tortured earth. These two panels flank a thoroughly chilling depiction of Ungoliantë emerging through a sheer, stony mountain cleft. An arrogant Melkor stands on a ledge, his arms crossed, waiting impatiently for her.

Howe paints Death’s heads on the body of the hideous creature, and this contributes to the horror – as if these are remnants of Ungoliantë’s many victims. Howe also uses flashes of reflected light to accent the creature. This sets her off from the rocks behind her in a subtle, yet terrifying way. The brooding red glow of the sky behind the monster creates an undercurrent of warning and dread. This is an altogether terrific picture – Howe’s one true unqualified winner in the calendar.

October: “The Drowning of Anadûnê” Whatever else can be said about Howe’s technique, one thing is for certain: he paints swell swells. His depiction of raging waters is unmatched here. The light – ranging from the cold blue-white of the sea spray to the greenish-brown of stormy heavens charged with lightning – commands complete attention. It is a disappointment, therefore, amid all of this realistic natural fury, that Howe limns an utterly lackluster temple drowning in the waves. The slightly skewed perspective of the temple is irksome. The structure, to put it simply, is not rendered very convincingly. While the smoke and flame rising from its apex is a persuasive detail, the temple itself is slick and antiseptic. So don’t bother looking at it – take in those terrific waves instead.

November:“Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” Howe captures a positively mythic atmosphere in this painting. A handful of ancient standing stones adorned with mysterious, weathered carvings help to properly set the mood, as do the hazy features of the deep background. In the lower left corner, Gawain’s patient, bent-necked horse, framed by the bare limbs of leafless bushes, bears echoes of N. C. Wyeth’s mediaeval illustrations. The stony-eyed Green Knight, ax in hand, is suitably enormous and threatening. He faces Sir Gawain, who bravely awaits the impending confrontation. This is a solid painting, one of the better ones in the calendar.

December: “Gandalf and the Balrog” This piece captures the sheer horror of this oft-depicted scene. The low angle of the observer allows for the looming Balrog to dominate the composition. The blue-gray and fiery red of the background, and the black and sable of the Balrog himself, all create a feeling of power and abject terror.

Two caveats: If Howe would have repositioned Gandalf’s left arm (with which he lifts his blazing staff), he could have shown the wizard’s face. This would have done a great deal to increase the picture’s impact. Also, Howe’s placement of a swath of smoke and the arcing curve of the Balrog’s wing over the bridge makes it appear as if Gandalf is the one standing on a mere tongue of the structure. It looks as if nothing exists behind the wizard, except the abyss below him. The effect is rather like Gandalf sawing off a tree limb-while sitting on the very branch which he is cutting. Clearly, this is not what Howe intended, but in an otherwise compelling picture, there it is. Resist the urge to snicker.

It is gratifying, in this age of flashing, fleeting images and blink-of-an-eye change, that HarperCollins provides us each year with a welcomed breather – a chance to walk without hurry the paths of Middle-earth. Although this calendar does have inconsistencies that keep it from being ranked amid the top Tolkien calendars, it does possess individual paintings that are alone worth its price. We can thank the publisher, the artist, and the Tolkien estate for such favors.